For many patients over at the Animal Medical Center (AMC) in New York City, the answer to that question looks much like the answers you’d give concerning your own close relatives: with state-of-the-art medical care and equipment, no matter what the cost might be.

Rachel St-Vincent, who is a veterinary radiation oncologist at AMC, treats patients with cancers too complex to address entirely with a scalpel. Using a linear accelerator (the same kind used in human patients) she designs targeted radiation therapies for tumors — which are often in hard-to-reach, delicate places like an animal’s nasal cavity or brain.

In order to treat Maia, a cat who has a lymphoma in her nasal cavity, St-Vincent has to build a detailed map of the cancerous and healthy tissue in Maia’s head. And for this cat, as for a human, the best option is, of course, a CAT scan.

A CAT scan (or computerized axial tomography scan) which uses X-ray images shot from a multiple angles to construct a three-dimensional map of a creature’s tissue density. St-Vincent uses that map to identify and target a tumor’s exact location in the body.

However giving a cat a CAT scan involves a few specific and unusual challenges.

A CAT scan requires that the subject lies perfectly still. Cats (and pets in general) aren’t very good at that. And so technicians anesthetized Maia so that they could begin the procedure.

Tubes ran down her throat and she was placed in the large machine, delivering air to her lungs.

In order for St-Vincent to aim the radiation beams precisely, Maia’s position in the CAT scan must exactly match the position in which they’ll place her in the linear accelerator.

A little shelf placed in her mouth is the very first step in immobilizing her head for this purpose.

Joseph Jacovino, who is a resident in the radiation oncology department, works to align the cat’s head as straight as possible in order to get the best possible scan.

Her body must be as straight as possible as well.

Next, the time has come to lift the cat’s upper jaw…

…and also time to prepare the goop

The goop is literally material for a mold of Maia’s canine teeth.

Later, the mold will help hold Maia’s head in this very position when she goes through radiation treatment.

Jacovino then presses his thumb on her head to get as deep a fit as possible.

Now, the time has come to rub the goop with ice so it will harden.

And now, the final restraint for Maia’s head is a mask.

Once it’s in place, only the cat’s ears are visible from the front of the machine.

A vacuum bag inflated around her body will hold its shape for the duration of her treatments as they help them position her body in this exact way in the future. The more precise her position, the better-targeted the radiation can be.

Jacovino now asks for the lights out, so he can confirm Maia is properly aligned using the CAT scanner’s lasers.

A sharpie marks just where on the mask those lasers landed.

Now Maia, covered in plastic and hot air to keep her warm as her metabolism slows under anesthesia, is completely ready for her scan.

Everyone must leave the room while the X-rays fire. Raf, a radiology technician, monitors the scan. Susan Lee, who is an anesthesia technician, keeps an eye on Maia’s vital signs.

The machine, which is built for humans, displays a 3D rendering of a human body.

However, Maia’s skeleton and tissues are soon visible.

As you can see, It takes a lot of machine to image a tiny cat.

Just a few hours later, Maia is awake and happy for some human contact in her cage.

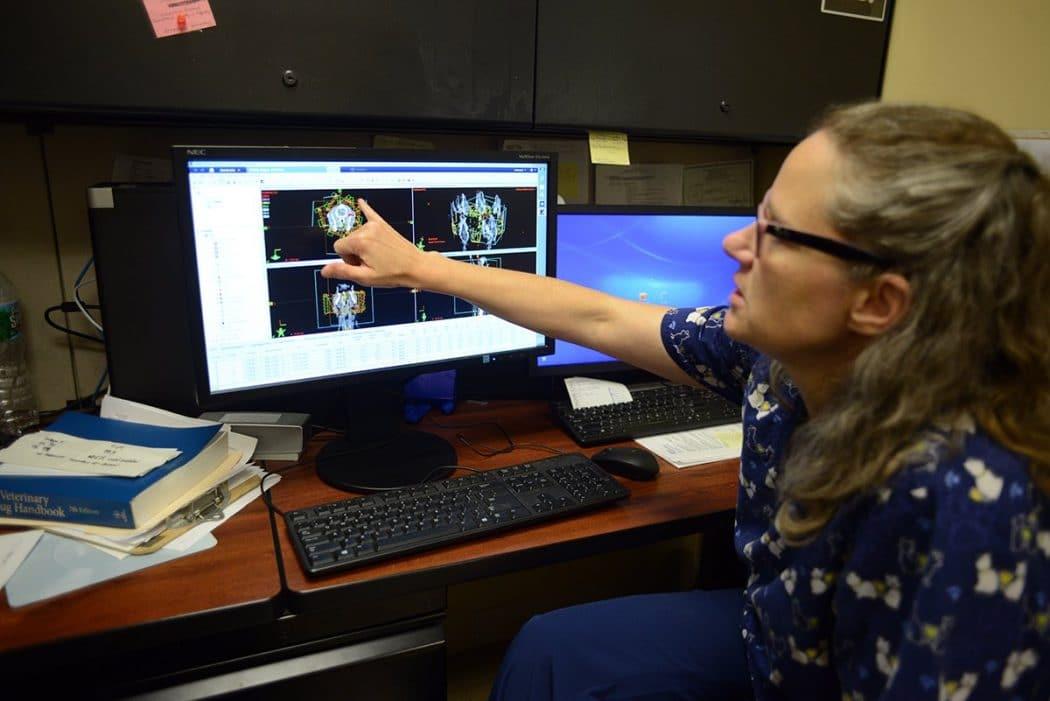

The next step is for St-Vincent to go ahead and analyze the scans and use them to design a plan for targeting radiation on the exact spot where Maia’s cancer resides

Radiation treatment can cure cancer in many animals, St-Vincent claims, but just like in humans “cures” are tricky to come by in oncology. In other cases, it could shrink or mitigate a tumor, making the animal more comfortable and perhaps even extending its life.